“I felt you drain the blood

From my left ventricle

Anytime you said you would

Change my heart into petrified wood.”

–Rural Alberta Advantage, “Drain the Blood”

A dinner of microwaved hot dogs topped with condiments from fast food packets, probably collected while Obama was still a senator, is followed by a luxurious high pressure hot shower, then sleep. Precious sleep. Although it feels like we rose early–the night gone in a blink as though it hadn’t just done another cosmic half rotation–the sun is already glaring across the dusty parking lot and scrublands that stretch as far as our grimy hotel room window enables us to view. In the distance, cars glide along the black asphalt of the highway, the sun reflecting like a shooting star as they disappear behind a far off ridge.

We make it to Petrified Forest and Painted Desert National Park not long after opening, yet the heat is already oppressive or impressive, depending on how you look at it. After waiting our turn in the now commonplace COVID line outside the visitor center, we have a nice conversation with the handful of rangers and park volunteers. After the boilerplate run down of what you can do in 1 hour, ½ day, full day, geared towards those who will wander no further than a 1000 feet from the park road, we ask the magical question that seems to unlock park rangers from their robotic trance the world over: what is your favorite longer or backcountry hike? Of course, this is followed by a few more questions, asked like you are trying to gain entrance to a 1920s speakeasy: have you hiked in the desert before? What is your fitness level? Have you ever been in the backcountry? How much water do you have? But, once these preliminaries have been satisfied, that familiar glimmer appears in the older, long-haired, white-bearded ranger’s eyes. “Well, my favorite hikes aren’t on the park map, but we have a few brochures that outline the routes. We just need to ensure that people are prepared, you wouldn’t believe how many people a year we have to go rescue, because they don’t take our warnings seriously.” Soon, we are gabbing away with the ranger, an older volunteer, and the gift shop worker, amicably arguing about the best ‘off the beaten path’ hikes, which are unmarked (yet semi-official) meanders into the backcountry. Eventually, a tacit agreement is reached, settling on the ‘onyx bridge’ hike as the best for us, along with a few additional, shorter ones if we still have the energy afterwards.

Muffled behind masks, the conversation is extremely pleasant and feels like the first positive interaction we have had in months. We laugh about and bemoan that most of the visitors to the park ask what they can do in an hour, usually a half day at most, which is basically to drive the nearly 30 miles of road and snap a few pictures at the overlooks. Most fly down the park road in a few hours, before returning to the highway, barely leaving the comfort of their car A/C. A pass-through park on the modern American, pass-through road trip. A recurring pattern emerges, after a few more park visits, where it becomes obvious that the NPS is being forced to cater to the instagram culture of the general public. All anyone wants to know is ‘how can I see the most beautiful sites in the least amount of time’. Of course, there has always been those dichotomous interpretations of the purpose of the national park system: is it for the people or for the protection of nature? Although it may have started under the mantra of ‘protection through education’, natural parks seem much more skewed towards the people these days, much to the lament of Edward Abbey (and most anyone that gives more than a passing thought to the importance of wilderness). As with any good employee, park rangers are always generally happy to cater to their paying public. But, during these rare personal glimpses and conversations–when not inundated with over-sugared kids and tired parents–there is a certain sadness or, maybe, frustration that seems to drip off every sugarcoated phrase.

At times I envy park rangers, who often appear to be living their dreams of spending their days outside in the most beautiful places on earth. At face value, is there anyone that seems to enjoy their job more, especially those park rangers in the lesser visited parks? They love to talk about their park–the flora and fauna; the geology and beautiful places–and always smile and just seem to be itching to get out there on the trail with you. Of course, many are retired volunteers, but it just makes me want to get on that bandwagon. Maybe I can transfer to the NPS or NFS for the last few years of my government service–satellite tag a mountain lion in Glacier; model a population of elk as they graze across the Grand Tetons. Then, retire and become a camp host for the rest of my golden years, living in a sweet sprinter van, putzing around in a golf cart all day, napping all afternoon, and cleaning pit toilets twice a day to earn my free accommodations. Yet, at times, after listening to rangers answer the same inane, mulish questions for the 10th time in 20 minutes, you begin to realize that it must naw at them slowly. Watching daily as we invade their cathedral, litter their altar, and slowly transform the wilderness they love into another asphalt snake of cars–a blight upon nature. A dream job, slowly transcending into a nightmare. I can’t help but wonder if the prominent displays of Edward Abbey books in western parks is a last bit of irony on the part of park rangers hobbled and enfeebled to do nothing against the continuous tide of tourists and bulldozers; their small piece of protest staring down the faces of those too dumb to even realize that they are being mocked.

We leave the rangers to the next wave of tourists clamoring about what they can do in two hours, asking what the best viewpoints are from the road. Although filled with anticipation to see the beautiful park and endless desert brimming with petrified trees, we can’t help but be weighed down, just slightly, by a general melancholy about the parks, people, things. Over the first bluff, the painted desert reveals itself across the horizon, a canyon opening up seemingly forever in shades of red, orange, maroon, and others that would make a box of Crayolas envious. We pull over stunned and just stare. Eventually we slowly move on down the road, I have to do everything I can to remember that I am driving a steel beast 100s of feet above a cliffside, as I am totally enamored with the scene literally unfolding as we move down the road. At the next viewpoint, our feeling of exasperation returns when we encounter a woman walking towards us on the phone in an animated conversation. She looks at us and says, “I guess he can’t be bothered to look up”. She was, apparently, referring to her husband sitting in a van in the parking lot who was on the phone and, we guess, too busy (or too lazy) to bother walking 100 feet to get a better view and enjoy the park from outside the confines of their wheeled vessel.

It was amazing to encounter this attitude continuously throughout the trip–people either too bored with nature, too lazy to leave the car, or too enamored with their phones to bother leaving their vehicle. One theory I developed was that easy access to an endless barrage of amazing photos, videos, and tv shows that highlight the most amazing sites in the natural world has somehow lessened first hand experience and cheapened the real world. Similarly, it seems that many people no longer differentiate first person perception from viewing photos online. It is as though their own eyes are not as impressive as an instagram filter and that, as opposed to many of us who think effort improves the experience, being forced to get out of the car and moving simply lessens the experience. I always go back to Edward Abbey’s theory that paving the national parks was, perhaps, the worst idea possible, because it cheapened the grandeur of our wild spaces and lessened the experience when one no longer had to endure long trips or arduous hikes to experience them. Of course, we simultaneously take advantage of this easy accessibility, while also cursing it. It is a blessing to be able to see the world’s most amazing sites by just driving up and hopping out of the car, but many times I find myself less impressed when I didn’t have to work to get there. Or, conversely, we become so spoiled that, for instance, by the time we reach the end of the Petrified Forest drive, we were too lazy to even get out of the car for short walks or scenic views, because it was ‘too hot’ (but really we had become so spoiled by the endless beauty that it no longer awed us or beckoned us out of the car). Obviously, there must be a balance between accessibility and effort to optimize both the enjoyment and appreciation of natural spaces, but where is that line drawn?

And so, we head off on the ‘onyx bridge’ hike, passing myriad warning signs about entering the backcountry badlands and leaving behind various groups of sweating, picture snapping tourists. As we descend 100s of feet into the painted desert, I can just envision the families watching us wondering what type of insanity would drive people from the safety of the A/C into the sweltering, shimmering heat of the basin below. I stared back, wondering what could drive them back into the inferno of their car and away from the beauty that lay ahead. Like Atreyu heading through the riddle gate in ‘The Neverending Story’, we emerge from a pair of red clay hills and enter a broad river basin that we must cross to enter the badlands where the majority of the petrified trees are to be found; we leave behind those tourists on the bluff behind, watching as we begin our journey. Eventually, after a hot, shadeless crossing, we reach the distant red cliffs and enter a narrow valley, slowly climbing through the labyrinthine passageways. Soon, we see petrified tree chunks poking through the sediment like wounded soldiers left on an abandoned battlefield. Every turn through the river bed unveils a new set of tree trunks and fractured pieces of age-old wood. Ascending to the canyon, we find ourselves atop a new set of badlands filled with a stunning array of sediment colors and endless petrified wood. The scenery is stark, yet colorful; intimidating, yet inviting. We burn and sweat in the unrelenting sun, waves of heat blackbody radiating off the red and brown stones at our feet passing through our bones like X-rays. But, the views and colors are simply astounding and we wander aimlessly filled with the adrenaline emanating from exploration of the unknown.

The size, amount, and mesmerizing colors of the petrified wood are simply beyond words. The onyx bridge–a large petrified tree spanning a small, dry riverbed–alone is worth the endeavour. Mixed with the emptiness, having such an expanse of earth to ourselves, and the endless unimaginable colors, makes up for the previous week of mishaps. All is forgotten, all is calm, quiet, empty. Perfection. We wander lost in the thought of what cataclysmic event took place here to bury such an enormous forest under sediment; the destruction and turmoil that led to the creation of so much beauty. I get the feeling that if I stand here another moment, I might never leave; that somehow this land will engulf me like the forest of old and turn me into stone. Reluctantly, after one last view across the vast valley below us and the badlands above us, we retreat back towards civilization, water, and A/C.

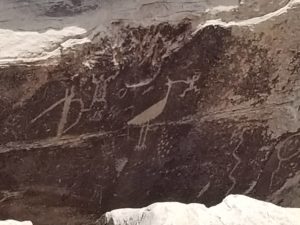

The rest of the park continues to amaze, but nothing can quite compare to the hike. Badlands of all shapes and sizes, cliffs and petrified wood of colors innumerable, and petroglyphs hidden on rocks abound. We meander through the rest of the park, stopping at every pullout, but too tired and hot for another long hike. We both agree that we were pleasantly surprised by the park–it receives little hype and barely registers compared to nearby attractions like the Grand Canyon, but, given the attention it deserves, it revealed beauty and sites that rival any other national park.

By late afternoon we hit the highway again, after stopping to grab our first takeout meal of the trip (subway from the rest area where we fill the gas tank of the Fordasaurus). We decide to power through to the north rim of the Grand Canyon and skip the crowds (and, maybe more importantly, the 6 hour detour) of the south rim. As the miles melt away, we desperately search for a place to stay near the north rim and, lo and behold, the north rim is surrounded by national forest, and has a campground at the top of a mountain pass equidistant from a number of great sites (the north rim, Vermillion Cliffs National Monument, and Kanab, UT). Thus, we set our sights on Jacob Lake Campground and set it on cruise control. As the canyons appear and disappear, red cliffs melt into pine forests, we finally start to feel like we are on the road trip of the west that we envisioned. Endless vistas come and go, mesas, huge cliffs, sandstone walls, canyons that appear out of nowhere, wasteland, but, somehow, life affirming wasteland. Then again, we can’t help but note as we drive through the waterless stretch of Navajo Nation that, as physically beautiful as it is, this unwanted, unlivable area is what we decided to ‘give’ (under coercion, war, and endless death) to the Natives of this unforgiving land. Forced to settle permanently on these desolate sandstone cliffs of nothingness, no longer able to pursue their semi-nomadic lifestyle, and watching as their ancestral lands in and above the Grand Canyon were turned into an amusement park for white people. The irony of our current quasi-nomadic lifestyle–moving every few years to satisfy some yearning for movement within us–was not lost. A part of me hoped that the signs announcing that Navajo Nation was closed to outsiders due to COVID might remain that way long after the virus had been tamed; that they might continue to milk us of our money through vice (gambling, cigarettes, booze), but keep what remained of their beautiful land to themselves.

As sunset glinted off the aptly named Vermilion Cliffs, we bulleted across the great Colorado River–a shiny beetle crawling along the landscape dwarfed by the enormous escarpment that we skirted. We ascended towards the North Rim and arrived at Jacob Lake campground just in time to claim a campsite and set up our tent, prepared for a few nights stay and relaxation. The last rays of sun set through the pines and a cool breeze wavered the branches causing us to dig out jackets and long pants as night settled at 8,000 feet.

Leave a Reply